Civilian Harm & the Russian Way of War: What Went Wrong?

Improvement in Russian battlefield behavior since the Caucasus conflicts in the 1990s has again regressed. Wherever this happens, humanitarian orgs need to ask why in order to address the trend.

Grozny after bombardment, early 1995. Photo courtesy of 24warez.ru via National Security Archive, George Washington University.

Taking a birds-eye view of the evidence, there has been a curious reversion in the Russian way of war over the last 30 / 35 years, assessed in terms of battlefield behavior, civilian harm and the humanitarian fallout it produces. Incipient improvements since the appalling, atrocity-laden warfare in the Caucasus of the 1990s were evident in 2008 during the Russia / Georgia war, but later reversed during both the 2014 and 2022 iterations of the Russia / Ukraine war into the present. Scholars and practitioners that work on this would do well to ask why, because beyond the political posturing, propaganda and apologetics aligned with one side or the other, no clear answers are particularly obvious.

It’s important to understand why because several decades worth of time, effort, and donor resources have been invested by the ICRC and other organizations into what used to be called ‘post-Soviet space’ to improve awareness of international humanitarian law among combatants and their political masters. These efforts are considered to be a long term investment that aim to moderate the behavior of combatants in armed conflict.

The ICRC typically excels at this work, and it is consistent with the ICRC’s usual mandate in every conflict. Beyond educating combatants throughout the chain of command about their legal obligations, they point out through high-level humanitarian diplomacy that, in violating IHL, combatants undermine their own military and political self-interests and ultimately make political settlement of conflict more elusive.

Given the extent of indiscriminate targeting of civilian areas in Ukraine, or indeed the apparent intentional targeting of civilian areas, these dissemination and diplomatic efforts seem on their face to have been ineffective. Why? It’s either that or we need to just assume that civilian harm would be worse if sensitization and IHL dissemination efforts hadn’t occurred. That is not an adequately robust proposition on which to base a major investment of time, effort and donor funding. A closer diagnosis of the problem will be a first necessary step before more effective mitigating measures can be identified.

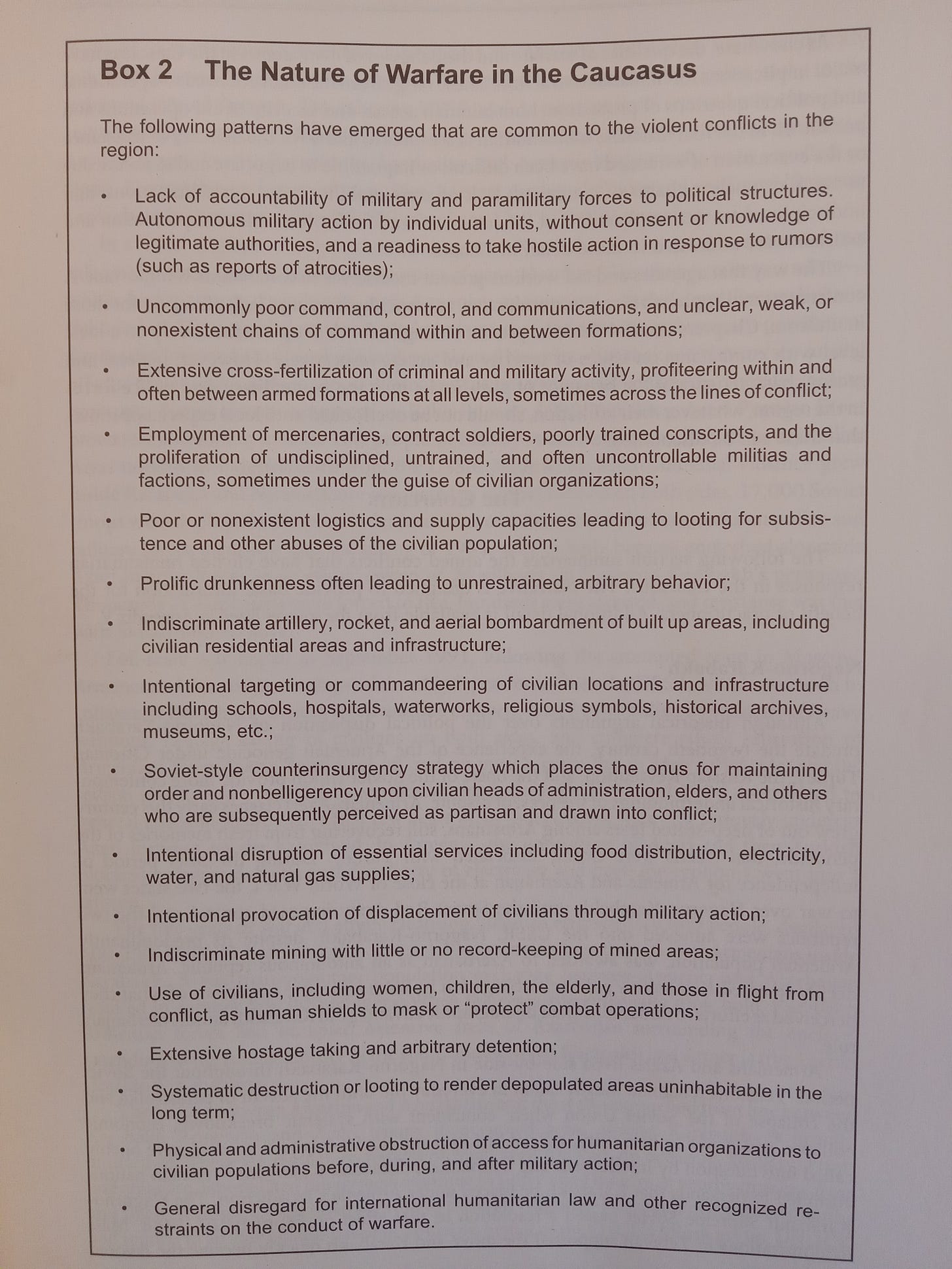

To go a bit deeper, the box below is an excerpt from a “Guide to Humanitarian Action in the Caucasus’ that I researched on the ground with humanitarian agencies and wrote in the 1990s. The guide was translated into Russian and distributed widely among authorities and practitioners in the region at the time. Comparing combatant behavior on the battlefield then and now, there are both striking similarities and some differences.

From Humanitarian Action in the Caucasus: A Guide for Practitioners, Greg Hansen, Humanitarianism & War Project, Watson Institute, Brown University, 1998.

The excerpt generalizes the nature of warfare and its humanitarian implications in the former Soviet space of the Caucasus throughout the 1990s, ending in about 1998. As such, it provides some behavioral benchmarks for comparison with more recent realities. It encompasses characteristics observed over that time period in several conflicts. Post-Soviet Russian forces were involved in all of them in some capacity: Georgia/Abkhazia, Georgia/S. Ossetia, Nagorno-Karabakh, Chechnya, and Prigorodnyi Raion. The behavior of military & paramilitary forces, including Russian, Abkhaz, Georgian, S. Ossetian, Karabakh Armenian & Azeri, Chechen and Ingush was observed across the spectrum of open warfare, nominal ‘peacekeeping’, and low intensity / frozen conflict, all occurring in recently post-Soviet space.

I took another field-based look at the humanitarian implications of Russian & Georgian military behavior in 2008/9 during and immediately after the brief Russia / Georgia war in S. Ossetia, Abkhazia & Georgia ‘proper’. Overall, human rights agencies have been critical of all parties in that conflict for violations of IHL, including the use of banned cluster munitions. But leaving aside the political question of the legitimacy or illegitimacy of the Russian incursion, humanitarian agencies active on the ground at the time — and with first-hand knowledge of combatant behavior — uniformly noted a general, marked improvement in Russian military behavior measured strictly in terms of its implications for civilian harm & protection, compared with the way wars were conducted in the region in the 1990s.

On the other hand, they were uniformly critical both of Georgian forces and South Ossetian irregulars, singling out Georgia’s use of heavy weapons in urban areas and indiscriminate targeting. Notably, by this time Georgian forces had been the recipient of considerable NATO training through the Partnership for Peace program beginning as early as 1994 and intensifying following the Rose Revolution in 2003. Georgian forces had also been rotating through deployments to both Afghanistan and Iraq as part of the US-led coalitions there, and were thus familiar (for better or for worse) with the American way of war as fought during the ‘Global War on Terror’. South Ossetian irregulars fighting against Georgian forces were, for their part, roundly criticized by neutral humanitarian and human rights observers for ethnic cleansing and other abuses of civilians in the conflict area.

Perhaps contrary to the impressions left by the bulk of media coverage, civilian harm in the Russia / Ukraine war is on a markedly smaller scale when compared with other current conflicts — notably Gaza1 and Sudan. Still, the level of destruction of civilian areas by Russian forces in Ukraine nevertheless stands out and has led to widespread suffering and distress. Given the extent of civilian harm, eventual reconciliation and reconstruction will pose immense long-term challenges once the war ends.

The city of Bakhmut is in ruins as a result of the Ukraine war. (Photo/Roman Playshko, Shutterstock)

What accounts for this change in Russian battlefield behavior over time? Not all the differences can be explained by conflict duration, geopolitical considerations or other such macro factors. Has there been a reversion back to Soviet-style ‘total war’ doctrine or some other doctrinal, policy or practice change? A collapse of targeting discipline? A culture change in the Russian military? Training failure? Leadership failure? A conscious political strategy pursued by Russian leaders in an attempt to shape the battlefield or the political outcome? Is it reflective of a more broad, global trend toward the degradation of respect for humanitarian law after the initial optimism of the post-Cold War period?

As civilian harm increases on today’s battlefields, humanitarian organizations active in every conflict need to do a better job of understanding the reasons for combatant misbehavior and its trends before they can hope to mitigate it more effectively. While some similarities and trends will be common across all or most conflicts, there will also always be context-specific reasons for greater or lesser civilian harm that need to be carefully diagnosed from conflict to conflict and across time. Only then can effective measures be designed to mitigate worsening civilian harm.